- Published on

Exceptions in Java

During the development of an application or library, it is often the case that we need to call another piece of code that might not behave as expected.

For example, imagine you were developing an application that allowed a user to delete a file stored on disk. We need to consider a couple of scenarios:

- What if the file didn't exist?

- What if the application doesn't have permission to delete the file?

Likewise, connecting to a database is another scenario where something might go wrong:

- What happens if the credentials are incorrect?

- What happens when the database is down?

To write safe code, we need a way to call the potentially problematic code without the world blowing up in our face when something goes wrong.

Often enough, the code that raises the fact that something isn't quite right is not code that you wrote yourself. This

is the case in the examples above - you'd delegate managing files to classes within the java.io and java.nio

packages, and connecting with databases to classes in the java.sql package. It will be these classes that figure out

that the file you're trying to delete doesn't actually exist, or that the database that you're trying to connect to isn'

t available.

Other times, you may have written the risky code yourself. Perhaps you have written an application service that allows a user to change their email address, and you need a way of telling the code calling the application service that the user who is changing their email address doesn't actually exist!

How do I know that I'm dealing with risky code?

Without being an expert in all of the potential error states of the functionality provided by library code you're calling, it is not always obvious what can go wrong. The good news is that it's not up to you, the client developer, to figure it out.

It is the developer writing the risky code who is responsible for declaring that something might go wrong. They have to say that something exceptional might happen. In other words, they have to declare that the method that they are writing throws an Exception.

Consider the following example code:

public Database connectToDatabase() throws DatabaseNotAvailableException {

if (connectionManager.isDatabaseAvailable()) {

throw new DatabaseNotAvaiableException();

}

return connectionManager.connect();

}

Notice that this code declares that it might throw a DatabaseNotAvailableException. In the event that the database is

not available, this exception is thrown, popping the connectToDatabase() method off of the call stack, and returning

the flow of control back to the calling method. If the database is available, the connection proceeds.

How do I handle the exception if it is thrown?

If you call a risky method, you'd better be ready to handle the risk! Most of the time, you'll be dealing with what are called checked exceptions. There's another type called - you guessed it - unchecked exceptions, which we'll come back to later.

You'll usually handle the exception by wrapping the call to the risky method in a try / catch block.

public long countItems() {

try {

Database db = connectionManager.connectToDatabase();

return db.executeQuery("count * from items_table");

} catch (DatabaseNotAvaiableException e) {

// Let someone know that something went awfully wrong.

return -1;

}

}

This says "try to do the risky connectToDatabase() operation, but if something goes wrong, return -1 instead".

The DatabaseNotAvailableException thrown by the connectToDatabase() method is caught by the catch block, and

handles it by returning -1. If the Exception is never thrown, the query is executed, its result returned, and the

contents of the catch block are never executed. (Note that returning -1 is probably not the best way to handle a

database not being available, it just allows me to illustrate the point without getting distracted!)

However, you are not obliged to handle the exception. You can, if you choose, pass the responsibility of handling the exception to the method that called you. You achieve this by declaring that the method also throws the exception, which is sometimes referred to as "ducking" the exception.

public long executeQuery() throws DatabaseNotAvailableException { // 🦆

Database db = connectionManager.connectToDatabase();

return db.executeQuery("count * from items_table");

}

In this scenario, the method that calls executeQuery() is responsible for handling

the DatabaseNotAvailableException. It could do this by wrapping the call to executeQuery() in a try / catch block,

or again passing the responsibility up the call stack.

When calling a method that throws a checked exception, these are your only two options. You either catch it, or specify that you throw it. In the Java world, this is known as "The Catch or Specify Requirement".

How long can pass on the responsibility for?

You can duck exceptions as many time as you like. Even your main() method can duck the exception if you really want it

to - your code will compile just fine. Just don't expect the Java Virtual Machine to handle it for you; it's not that

clever. It will just shut down if and when it comes across such an exception.

What is an exception anyway?

Good question. Did you notice the throw new DatabaseNotAvaiableException() in the example above? It looks like we were

constructing a new object. In fact, we were. Exceptions, are just a special type of Object. More precisely, they are

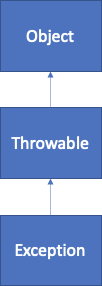

objects which extend the Exception class, which itself extends the Throwable class.

You won't usually throw an instance of the Exception class itself since it is too generic. Instead, you want to

provide the context behind what has gone wrong by subclassing either Exception itself, a built in subclass

of Exception such as a LogicException, or a subclass of one of your own exception types.

Does that mean I can throw more than just Exceptions?

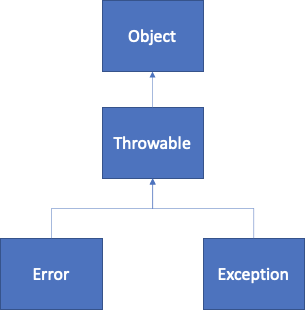

Yes! There's another type that extends Throwable - Error. The class hierarchy actually looks like this:

It's quite likely that you'll never throw or catch Errors yourself though. They tend to be used for problems that affect the JVM itself, and so aren't involved in day-to-day application development.

Unchecked Exceptions

Problems like a database not being available or a file not existing could happen at any time and need to be handled within your application code for when the worst happens. However, other problems, such as accessing an index of array that does not exist, are simply just the result of programmer error. In an ideal world, you would never write code to handle those cases, you would just not write the bug in the first place.

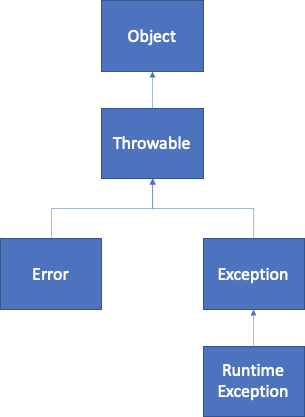

For times when an API is used incorrectly in this way, a special type of exception, known as a runtime exception, can be

thrown. A runtime exception is simply an instance of the RuntimeException class (or a subclass of it), which itself

extends Exception.

Along with instances of type Error, instances of type RuntimeException are known as unchecked exceptions. This is

because The Catch or Specify requirement does not apply to them. After all, if you've made a programmer error, you are

much better off writing code to fix the bug than writing code to handle the exception caused by the bug. That said, you

can still catch runtime exceptions if you want to. There's nothing stopping you.

Chained Exceptions

Recall the example above where we tried to count the number of items in a table, and where we returned -1 if the

database was not available.

public long countItems() {

try {

Database db = connectionManager.connectToDatabase();

return db.executeQuery("count * from items_table");

} catch (DatabaseNotAvaiableException e) {

// Let someone know that something went awfully wrong.

return -1;

}

}

In reality, returning -1 is far from ideal. What does -1 mean? Is there a negative count? Can -2 also be returned?

It would be far better if we communicated the issue back to the caller, but how do we achieve this without leaking low

level implementation details through our nicely layered architecture?

To maintain our levels of abstraction, we want to keep our exception classes aligned with the level of abstraction we

are currently in. Suppose that the above method existed within a class called SqlInventory that implements

the Inventory interface. Application services interacting with an inventory don't want to concern themselves with

exceptions about a database. For all they know, the underlying implementation of the inventory might use a file-based

storage mechanism, or a third party API.

We can avert this problem by instead throwing a new exception that's aligned with the language of the inventory, perhaps

an InventoryException.

public long countItems throws InventoryException () {

try {

Database db = connectionManager.connectToDatabase();

return db.executeQuery("count * from items_table");

} catch (DatabaseNotAvaiableException e) {

throw new InventoryException("Database not available");

}

}

But what about all the information stored within the DatabaseNotAvailableException? We've just thrown it all away,

never to be seen again. This is where chained exceptions come in.

The various Throwable constructors allow us to pass a causing exception in as a parameter, letting us to "chain" the

exceptions together.

public long countItems() {

try {

Database db = connectionManager.connectToDatabase();

return db.executeQuery("count * from items_table");

} catch (DatabaseNotAvaiableException e) {

throw new InventoryException("Database not available", e);

}

}

Now, when logging the existence of an InventoryException further up the call stack, the getCause() method declared

in the Throwable class can be called to retrieve the DatabaseNotAvailable exception and log the additional

information contained within it.

Conclusion

Dealing with errors when programming is part of the job description. Databases fail, networks are unreliable, and files become corrupted. Exceptions allow us to handle these errors elegantly, enabling the normal flow of our code to stay focussed on the task at hand, and letting us explicitly deal with the exceptional cases independently.